After the unification process of 1918, in the former Hungarian State schools Romanian language was introduced as a teaching language. Consequently, the Hungarian as a teaching language was solely preserved in the vocational schools. The governments showed little understanding toward the minorities' vocational schools, aiming rather at the unification of the scholar system. The Roman Catholic Church sustained and administrated hundreds of elementary and secondary schools, many of them having a multi-secular history. Based on the documents from the churches' archives, this study presents the efforts of the Roman Catholic Church to preserve and maintain all these schools.

Up to 1918, the institutions of the Roman Catholic Church in Transylvania had maintained a dominant position, with the overwhelming majority of the Hungarians in the Austro-Hungarian Empire members of this church. Moreover, although the separation between State and Church had been operated following the confrontations of the 1890s, the Church continued to exert its influence over society and culture, especially at the educational level. Not surprisingly, considering the overall political atmosphere inside the Monarchy, the church institutions played a tremendous role in the Transylvanian society. The state tried through all means to enlarge and expand the networks of schools under its direct control and sustenance. Nevertheless, the denominational education in the province succeeded in securing an influential and patronising position in most

JSRI • No.3 /Winter 2002 p. 115

activities. During the latter part of the dualist period, the state administered as little as 30% of the overall number of the primary and secondary schools in Transylvania.

As for the organisation of the system, no radical changes had occurred. The old structures of the Roman Catholic Church had been preserved. However, before the union of Transylvania with Romania, many parishes belonging to the dioceses of Satu-Mare and Oradea were included in Hungary in consequence of the new frontier lines and the subsequent application of the "aeque principaliter" principle - two dioceses governed by one bishop. The same principle had also introduced the administration of a diocese by a non-resident bishop. A similar situation could be found in the diocese of Cenad. Here, however, no change in the structure of the diocese was operated, unless we count as one the change of name from the Cenad diocese to the Timisoara diocese, prompted by the fact that between the World Wars the name used had been that of the latter.

As mentioned before, the Roman Catholic Church was one of the most important historical denominations in Transylvania, with a particular status within the social and economic relations in the region. It maintained an important school network, which in the Ciuc area was exclusive. Moreover, the Roman Catholic Church also patronised a wide range of secondary schools, all of them centuries old. In the beginning, the Roman Catholic Church took upon itself to catechise and educate the younger generation.1 These were the fundamental objectives of the activities carried out by its parishioners. The role of catechisation was to integrate the teaching and moralising strength of the Bible into the life and culture of the people. It was only logical, then, that the educational role of the church was performed by schools - the place to assimilate culture. It is precisely through this activity that the Roman Catholic Church played an important social and cultural role in the historical evolution of Transylvania.2

Following the Union of 1918, which among others granted the Romanians in Transylvania the right to self-determination, both the situation and the status of the Roman Catholic Church changed radically. The parishioners were mostly Hungarians and partly, Swabians. They too had undergone radical demographic changes. Prior to 1918, the Hungarian population was the dominant ethnicity and enjoyed the full co-operation of the state authorities, whereas after the formation of the Romanian State, they became the minority. At denominational level, the Roman Catholic Church held the dominant position in the former Hapsburg Empire, with the vast majority of the inhabitants being Roman Catholic. Then, it became just another church among a group of more within the Romanian State, functioning alongside the dominant Orthodox Church and the privileged Greek Catholic Church of the majority.3

The Roman Catholic Church examined the emerging situation and soon designed new tasks for the given conditions. Preserving and developing its network of schools and other educational institutions became a priority. This is how bishop Márton Áron underlined the responsibilities of his generation: "We have a special

JSRI • No.3 /Winter 2002 p. 116

duty bestowing upon us a heavy responsibility. Yet, future will give the

measure of our actions and judge us by the values we have created and

developed in the process of fulfilling our present mission. We are the

artisans of our own destiny, and we can expect nothing from life but what

we achieve through consistent, hard work. We have to discard our indolence

(…) we have to exist in order to shape a generation that should meet

the requirements of our times…"4

The activity in the educational field

of the Roman Catholic Church and of other denominations was directly determined

by the changes occurring in the social and political life of the Romanian

society. Throughout the period between the World Wars, especially in the

first decade, the efforts of the Romanian State were directed towards

the unification of the economic, legislative and cultural spheres. The

Romanian political parties envisioned different manners of accomplishing

and promoting these goals. The phenomenon translated into a climate of

instability in the political life of the country, the arena of confrontation

for two important parties: the National Liberal Party (NLP) and the National

Peasant Party (NPP). The impact was notable in the activity of the Roman

Catholic Church, too. It was best illustrated in the approach to the minority

problem: the NLP adopted a unifying centralising politics, whereas the

NPP advocated a regional-oriented politics.

The Romanian public opinion also reflected

the two parties' conflicting ideologies on the minority issue. An expert

in the epoch's history and ideologies asserted From the start, the liberals had declared

Romania an indivisible national state, definitely not multilingual, which,

in accordance with the universal liberal doctrine, provided the equality

of freedom and rights for all citizens. Therefore, the liberals considered

that at the very foundation of democracy and of a full-fledged state lay

the individual rather than collective rights.6 The NPP's tenet

endorsed a distinct approach to the issue of minorities, but deemed it

unnecessary to promote specific minority policies in Romania. Thus, the

idea that there was no minority issue in Romania became a generalised

viewpoint. Naturally, the apolitical Romanian society had readily embraced

the idea.7

After the Union, Romania underwent a process

of "building the nation", that is, the genuine process of unifying

the state.8 Referring to the diverging opinions surrounding

the national processes, István Bibó said: "The national

frame in Eastern Europe was something to work on and rehabilitate, something

to achieve and permanently defend not just against the existing dynastic

state, but also against the partial popular indifference colluding with

a wavering national consciousness. This situation generates the dominant

feature of the unbalanced political spirituality of Central and Eastern

Europe: apprehensions about the existence of the community".9

Thus, the building of a nation occurs within the frame of an existing

state10, and according to Bibó's

JSRI • No.3 /Winter 2002 p. 117

that the policy generated dissatisfactions among the minorities, even

in such matters as the choice of terminology, as was the case of the term

"foreigners", deemed derogative.5

thesis the setting up of democracy is hesitant in the East European states

because of these apprehensions. As a result, nationalism is embraced by

the entire society. After the unification process, the Romanian governing

political forces considered that the new frame should undergo a radical,

rapid and sustainable cohesion. The need for a national elite was dramatically

felt, leading to an intercession by the state. Moreover, some social categories

immediately enjoyed advantages that theretofore had counted as privileges

for some ethnic groups. Such changes affected especially the Hungarians

in Transylvania. The necessary adjustments made within the government,

the state administration and the social and economic life were, eventually,

reflected by the relations between the several minorities and the majority.

Yet, the official politics of the state was met with sharp criticism.

Traian Bratu, the dean of the University of Iasi, renowned in the World

Wars period for his opinions on the status of minorities, stated that

the foundation for any state was equal rights for all citizens, to be

achieved only if all the citizens were loyal to the state. This goal would

only be ruined by hatred or by granting privileges to some over others.11

All speciality literature dealing with the issue of nation and nationalism

emphasises that education and culture are paramount in the process of

building a nation. The development of the school network in order to create

a new elite was sustained by the state; in fact, this was part of the

cultural enterprise having for its main objective unification and the

eradication of regionalism.12 This policy also affected the

activity of the Roman Catholic Church. However, as pointed out by an important

expert in inter-ethnic relations, nationalism has never been a major issue

with the varied ethnic communities in Transylvania, contrary to what the

politicians have purported.13 The legislation concerning education

and the school system issued during the World Wars established the course

of development for the Roman-Catholic denominational education under the

auspices of the Roman Catholic Church. As the schools were the most effective

tools for preserving national identity, the topic ignited hot debates

and led to conflicts of interest. Mikó Imre, one of the few specialists

in minority law stated: "Most important among the minority rights

is that regarding the schools for the citizens of ethnicity other than

Romanian. In the case of the minorities, school is the agent that ensures

the survival of the mother tongue and culture, and instructs the younger

generations in the awareness of ethnicity. This is the source of all the

problems and arguments surrounding the institutions of learning."14

On analysing the legislation pertaining

to education, one can easily observe that the main laws formulate the

general setting for the instruction of the minorities. By 1923, the Constitution

of 1866 was still in effect, while its provisions were expanded to include

Transylvania. Still, in this part of the country, the Directory Council

elaborated a full set of measures and regulations. This eventually led

to the enforcement of a particular variant of the law. The Constitution

of 1923 made general prescriptions regarding the freedom of education,

making no reference to special measures concerning the minority

JSRI • No.3 /Winter 2002 p. 118

educational system.15 Paragraph 24 stipulates that the right

to education is provided for all the citizens of Romania by law, unless

it conflicts with ethics and public order.16 Yet, the Constitution

of 1938 does not safeguard unrestricted and equal access to education

for the minorities. Under the royal dictatorship, all of the laws and

regulations regarding the minorities were compiled into The Status

of Minorities.17 Furthermore, minorities could found schools

under the more general law regarding private education. The Churches could

lay the foundation of private schools only by civil right.

In many respects, the Romanian legislative

system, as is the case of the minority's right to education, was in consonance

with the international law system. International law included the principle

by which providing education in the mother tongue is the way to

preserve the minority's national specificity, language and religion. This

principle was also promoted by the Treaty on Minorities, signed by Romania

on December 9, 1919 in Paris. The treaty safeguards the right to teach

and learn in the mother tongue, as well as the setting up and administration

of institutions of education and culture, and the unrestricted use of

the mother tongue.18 However, the treaty did not endorse any

special rights for the private schools. The state had the right to supervise

and check such schools, whereas the minorities were under the obligation

to administrate them. It was also the duty of the state to subsidise these

schools. The treaty on minorities admitted as absolute the right to teach

and learn in the mother tongue, that is, the treaty needed no further

approval by the State. Traian Bratu had underlined this feature of the

treaty, maintaining that to observe this legal document was mandatory

for Romania to be integrated among the `civilised' states of Europe.

An international document playing an important

role in the activity of the denominational education was the Concordat

signed between the Romanian State and Vatican. This document came in effect

in July 1929, and was paramount in settling the relations with the Holy

See. It is noteworthy that the first paragraph of Article 19 stipulates

that the Catholic Church has the right to found and subsidise elementary

and secondary schools under the jurisdiction of a bishop, with the supervision

of the Ministry of Education.19 The Concordat also stipulated

that the denominational schools under the jurisdiction of a bishop had

the right to choose the language of teaching. The Concordat had

brought hope among the Catholics, in a country with a prevailingly orthodox

population.20

1924 was the year when the first laws

were issued regarding the minority education during the World Wars. The

Romanian government saw the necessity for a merger of the educational

system: the law regarding the public elementary education and the grammar

schools. This law was paramount for the educational system. As for the

minority rights, the above-mentioned law laid down the principles to follow

by the laws to come.

The law extended to seven years the duration

of elementary education, emphasising its compulsive character. The law

was also meant to eradicate the differences

JSRI • No.3 /Winter 2002 p. 119

of the four distinct educational systems. The initiator of the law himself

- C. Anghelescu - admitted that the goal of the law was to unify and harmonise

the educational system, but also to awaken national consciousness.21

As noticed by an observer, the Romanian government officials were aware

that public education was the institutional component with a dramatic

impact on the fate of a nation, on its cultural and spiritual growth.22

Under the law, the teaching language was

Romanian, and in the regions where the mother tongue of the inhabitants

was not Romanian, the Ministry of Education set up schools in the corresponding

languages. Nevertheless, Romanian language was compulsory in these institutions

too. Hot debates were ignited by some provisions of the law, such as Paragraph

8, which stipulated that the Romanian citizens who did not speak Romanian

were under the obligation to enrol their children in either public or

private schools in the Romanian language23. This had in view

the Szeklers, whom certain historians and linguists had misinterpreted

as not Hungarian, but rather Hungarian-made, and who had taken up Hungarian

for their mother tongue. This phenomenon led to questioning the identity

of an important part of the Hungarian inhabitants. It was stated that

names such as: Ráduly, Szakács, Szûcs, Kurta, Farkas

were of Romanian origin.

Fiery debates were prompted by Paragraph

159, too, which stipulated that schoolteachers and other school employees

coming to teach from counties outside those newly united would benefit

from a 50% rise in wage. In fact, the underlying issue was the founding

of the so-called cultural areas, which were decisive in the process of

re-structuring the educational system in these territories.24

The coercive decision for the Hungarian

community to support the state schools had also generated passionate debates,

as the community had already had trouble ensuring that the activity of

the denominational schools preserved their ethnic identity. The law of

the private schools, which had regulated the situation of a large category

of schools, did not acknowledge the specific and traditional character

of the denominational schools. They were considered private schools. Despite

a long series of debates and petitions submitted to the United Nations

while the law of December 22, 1925 was still in draft, the representatives

of the minority failed to have the denominational schools nominated and

recognised under the law. Following negotiations with minister C. Anghelescu,

it was agreed that under the provisions of the law the minority pupils

can be enrolled in denominational schools - considered private schools

- or in schools set up by private people, in addition to enrolment in

state schools. The negotiations also stipulated that private schools must

obtain a special license to function from the Ministry of Public Instruction.

By law, these schools were under the direct guidance and supervision of

the Ministry. Another stipulation that played an important role and influenced

the minority education provisioned that the pupils from private schools

must take their examinations in the state schools. As regards the teaching

language, the law

JSRI • No.3 /Winter 2002 p. 120

specified it to be Romanian for the Romanian or Romanian-born children,

whereas for the other ethnic communities, the teaching language was the

mother tongue of those enrolled in private schools. The denominational

Catholic education suffered a great loss at the hand of certain provisions

of the law under which the schools supported by monastic orders and congregations

must use Romanian as the teaching language, with the result that many

ceased to exist altogether. Further difficulties arose when Geography

and History were taught in Romanian.

Private schools did not have the authority

to issue diplomas. There were cases where the Ministry conferred the authority

to the private schools, with the specific provision that no denominational

school could secure such status. The graduates of the Hungarian denominational

schools had to pass their examination and obtain diplomas from the state

schools. The law concerning private schools authorised the grammar schools

set up before 1918, on condition that they observe the general norms imposed

on private education25.

It is noteworthy that the law was considered

a liberal and tolerant legislative initiative. This was the interpretation

given especially by the Romanian press and the speciality literature.

The minorities challenged the law initiated by Minister Anghelescu in

what concerned the allocation of funds, the restrictions on the usage

of certain books, maps, and manuscripts banned by the Ministry of Education,

the interdiction to benefit from external financial assistance.

The law of school graduation passed in

March 27, 1925 had both short- and long-term effects on the minority educational

system in general and on the denominational one, in particular. The law

specified the obligation to pass the graduation exam in the Romanian language

in order to issue a state diploma or some other document testifying the

graduation of the secondary school. The law caused a high incidence of

school failure among the minority pupils. According to statistics, 70-80%

of the candidates failed their exams in the first year.26

The legislative frame was also valid for

the Hungarian Catholic education, later modified by the laws of 1928 and

1939.

The network of the Roman-Catholic schools

underwent essential changes after the Great Union (1918). Following the

provisions of the Peace Treaties, the state schools in Transylvania were

integrated within the Romanian school system. The pupils from 1,318 state

schools with Hungarian as the teaching language chose to attend the 755

Hungarian denominational schools.27 The situation would have

been acceptable if the number of denominational schools had been increased.

Both the Romanian legislative system and the lack of political will had

hindered this process. A further factor was the refusal by most schoolteachers

to take the oath as required by the Romanian authorities.

In the years following the Union of 1918,

the Hungarian churches established 403 elementary schools, of which 61

Roman-Catholic, 33 public schools, 7 secondary schools, 7 commercial secondary

schools, 4

JSRI • No.3 /Winter 2002 p. 121

pedagogic schools, and 1 pedagogic secondary school.28 This

engaged an important financial effort on the part of both the Hungarian

minority and the attending churches. Even the Minister of Public Instruction,

C. Anghelescu, appreciated the effort. Starting with the 1919-1920 school

year, the denominational schools included in their syllabus subjects which

were national in character: Romanian language and literature, the Geography

and History of Romania. At the time of the Directory Council, the school

policy undertook to incorporate the specificity of the Transylvanian society

and the history of the educational system in this part of the country,

the denominational schools included.29 After the revocation

of the Directory Council, this distinctive situation was ignored. In sharp

contrast, the educational system was gradually centralised. The Hungarian

educational system in Transylvania was subordinated to the Ministry of

the Public Instruction, whose policies differed radically from those of

the Directory Council. The Ministry and the authorities in Bucharest envisaged

an increase in the number of public schools.

The Roman Catholic education proceeded

differently during the inter-war period as compared to the pre-war period

when the Roman Catholic Church held a dominant position within the state.

The vast Austro-Hungarian Empire was prevailingly Catholic. Afterwards,

the Roman Catholics of Great Romania became citizens of an Orthodox country

with a nationally dominant Orthodox Church. This affected the denominational

educational system of the other Churches in spite of the promise made

by Onisifor Ghibu, the leading anti-Catholic, to safeguard the rights

of the educational systems other than in the Romanian language. "There

will be absolute freedom and everyone will have the right to set up as

many schools as they wish".30 In January 1922, the Minister

of Instruction promised that there would be no actions to repeal the Hungarian

schools and the authorities would not interfere with the internal issues

of these schools, for the government was fully aware of the importance

of their educational system.

The measures undertaken by the government,

however, were the opposite. A language certificate was required of the

teachers belonging to the minorities. The Hungarian teachers did not benefit

from funds allotted to teachers belonging to other educational systems.

There was no retirement program for teachers at the denominational schools,

and there was an interdiction to enrol pupils of nationalities other than

Hungarian. The seminaries were under the obligation to use Romanian as

the language of teaching. These provisions drafted by C. Anghelescu led

to serious protests on the part of the non-Orthodox Church representatives,

who petitioned the Minister and King Ferdinand.31

On December 24, 1923, the representatives

of the minority churches held a meeting at Alba Iulia in order to promote

such actions as would ensure the functioning of the denominational schools.

At the proposal of Majláth Gusztáv Károly, the Roman

Catholic bishop, they decided to require a hearing by the Minister. Minister

Anghelescu considered the initiative belated, for all the measures taken

by the Romanian State sought to secure

JSRI • No.3 /Winter 2002 p. 122

the learning of the official language and to hinder the process of de-nationalisation.32

Moreover, the situation of the denominational schools was aggravated by

the obligation to take the degree examination in Romanian. This led to

70-80% failure.

There was much hope about an improvement

in the functioning of the denominational schools, when the Liberal Government

was replaced by the National Peasant Party Government. It was believed

that the NPP Government under the leadership of Iuliu Maniu would try

to find a solution to the problem, which, however, was left unchanged

with the exception of funding.33 If we examine the figures,

we will see that from 1919 to 1924, 2,289 public Hungarian educational

institutions were repealed. These were elementary schools, public schools,

secondary schools, pedagogical schools and commercial schools. It was

estimated that after World War I there were 330,000 Hungarian children

eligible for school in the United Territories, Transylvania and Banat.

It was for the Hungarian churches to provide the education for these children.

Over a period of some years, the churches set up 403 new elementary schools,

of which 61 were Roman Catholic. The number of the Lutheran and Unitarian

schools also increased when the Roman Catholic Church underwent financial

difficulties.34

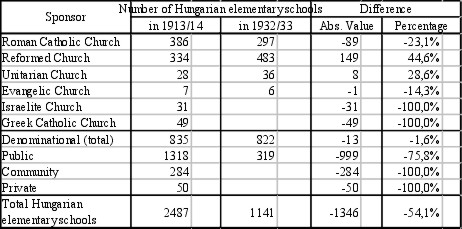

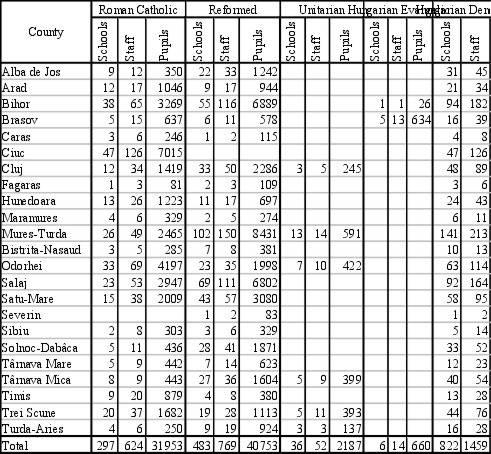

The following table shows the history

of schools in Transylvania:

Table 1. Sponsors of elementary schools

in Transylvania

Apparently, the situation of the Hungarian denominational schools was even worse than that of the Romanian

JSRI • No.3 /Winter 2002 p. 123

denominational schools in these provinces prior to 1914. In 1914 there

was 1 Romanian school to 1,007 Romanian inhabitants, while according to

the census of 1930 there was 1 denominational school to 1,647 Hungarian

residents in Romania.35

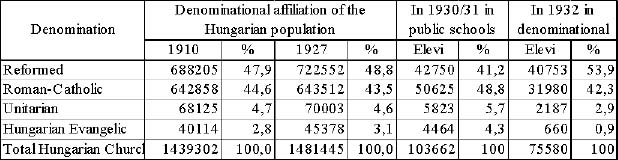

From 1930 to 1931, there were 76,255 children

enrolled in the denominational schools out of a total of 180,029. This

represented 42.4% of the overall number. The causes were varied: families

with financial difficulties, limited possibilities for the churches, or

the enrolment of many Hungarian children in public Romanian schools. Romanian

surveys of the period showed that in the 1927 school year there were 838

denominational schools registering 89,421 pupils: 49,841 were of Hungarian

nationality and 25,978 were Roman Catholics. In 1932, 53,9% of the pupils

enrolled in elementary denominational schools were Calvinists, 42,3% Roman

Catholics, and 2,9% Lutherans. The decrease in number was explicable due

to the waning finances of the Catholic school sponsors. The Roman Catholic

Church was severely affected by the 1921 agricultural reform. Look at

the following table comparing the categories of pupils and schools by

counties36:

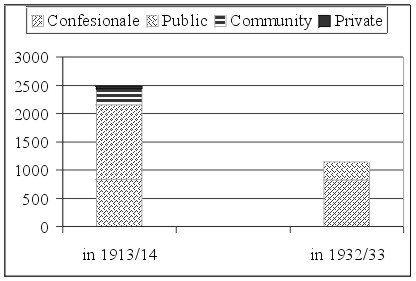

Figure

1. The number of elementary Hungarian schools in Transylvania.

JSRI • No.3 /Winter 2002 p. 124

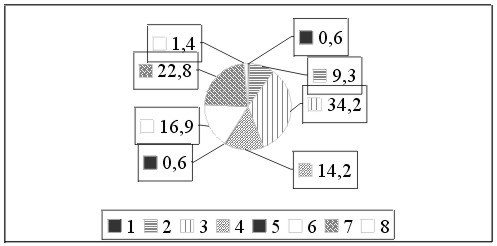

Public nursery schools with Romanian as the teaching language

Elementary public schools with Romanian as the teaching language

Elementary public schools with Hungarian as the teaching language

Denominational nursery schools

In Roman Catholic schools

In Calvinist/Lutheran schools

In Unitarian schools

In Evangelic schools

Table 2. Distribution of pupils of the elementary denominational and public schools compared to the denominational affiliation of the Hungarian population.

Figure 2. The number of pupils enrolled in elementary schools in Romania 1930/31.

JSRI • No.3 /Winter 2002 p. 125

Table 3. Elementary Hungarian denominational schools in Transylvania in 1932

JSRI • No.3 /Winter 2002 p. 126

Table 4. Public schools with Hungarian as the teaching language (1918-1927)

27 pedagogic schools in Hungarian in Transylvania in 1918, whereas in 1928 there were as few as 8 left. In 1918, 13 out of the total number of pedagogic schools belonged to the Roman Catholic denominational education, whereas by 1928 there had remained only 5: 1 pedagogic school for boys in Miercurea- Ciuc, 1 pedagogic school for girls in Sibiu, 1 for nursery school teachers in Oradea, 1 pedagogic school for girls in Oradea, and 1 pedagogic school in Satu-Mare. The pedagogic school of Miercurea-Ciuc functioned at ªumuleu Ciuc until 1923, and was the most important educational institution qualifying teachers for the denominational schools and deacons for the Roman Catholic churches.37

The survey data for this type of schools point out that, in Transylvania, there were 4 schools qualifying Hungarian teachers, of which 2 were Roman Catholic, 1 Calvinist, and 1 Lutheran, in the 1926-1927 school year. 307 pupils were enrolled in 4 pedagogic schools for boys: 119 Catholics, 76 Calvinists, 110 Lutherans, and 2 Unitarians. There were also 9 pedagogic schools enrolling 601 girls, of which 195 were Roman Catholic. The Hungarian churches were in charge with the administration of the maintenance of the pedagogic school.38

The Public Schools were of utmost importance for the educational system as they addressed the lower middle class bourgeoisie. These schools trained the pupils in the basic scientific and practical knowledge. According to the above-mentioned data, in the 1926-1927 school year there were 9 denominational public

The tables show that the majority of the Catholic schools were located

in counties such as Ciuc, Odorhei, Mures-Turda, that is, in the regions

populated by Szeklers, yet there were many elementary Catholic schools

which had also functioned in the Western regions of the country. The dissemination

area of these schools was closely related to the dissemination of the

Hungarian population, particularly to the denominational affiliation of

the communities.

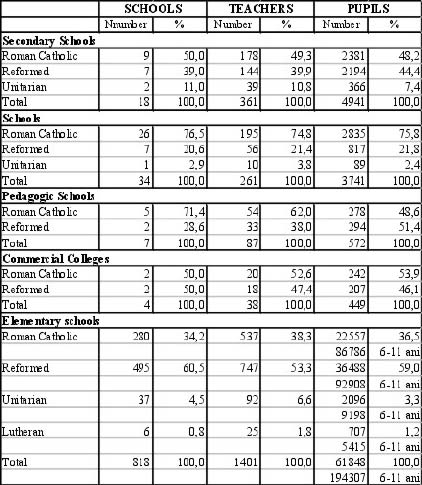

The secondary education was characterised by great diversity in schools and the fluctuating number of pupils. This type of instruction played an extremely important role in forming an elite, and this is precisely how the Hungarian elite had formed between the World Wars. This system had also safeguarded the national identity. According to statistical data, there were

JSRI • No.3 /Winter 2002 p. 127

schools, of which 2 were Roman Catholic. Most importantly, just prior

to the war, public schools totalled 106, of which 46 were Roman Catholic.39

JSRI • No.3 /Winter 2002 p. 128

The year 1919 was a turning point in the existence of the secondary schools.

This was the year in which the authorities abolished the teaching in Hungarian

language in 11 of such institutions. In the school year 1926-27 there

were 25 secondary schools - denominational secondary schools for boys,

of which 10 were Roman Catholic. The number of pupils enrolled was 4,373,

of which 2,523 were Roman Catholics. There were also 5 secondary schools

- denominational secondary schools for girls, of which 4 were Roman Catholic.

The number of Catholic girls enrolled was 622.40

The Hungarian commercial schools with

tradition had ceased to exist. The three commercial colleges in Timisoara,

Orãstie and Târnãveni were extremely important for

the Roman Catholic community of Transylvania.41

The following table illustrates the situation:

Table 5. (see previous page) Centralised

data on the denominational schools in 192842

As shown by our analysis, the Roman Catholic

denominational education was confronted by serious problems between the

World Wars. This type of education was specific for the Transylvanian

region. The general impact of the process of unification and centralisation

the Romanian authorities had embarked upon also affected the Roman Catholic

denominational school system from a juridical, institutional and economic

perspective, alike.

Notes:

Traslated by Ana-Elena Ilinca

1 See Catechezii Tradende, in Korunk

hitoktatásáról , vol. II, Szent István Társulat

[The Society of Saint Steven] Budapest, 1980. pp. 224, 247-249.

2 Általános Katekétikai

Direktórium [General Guide on Catechization], ibidem, p.42.

3 For further discussion, see: Irina Livezeanu,

Culturã si nationalism în România Mare 1918-1930,

Humanitas, Bucuresti, 1998.

4 Márton Áron: Templom

és iskola , in: Erdélyi iskola , VII, 1939/40, 3-4,

p.126.

5Livezeanu, p. 289-347, work quoted

6 Seaton-Watson, R.W., History of the

Romanians, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1934, p. 549-550.

7 See: Livezeanu. Work quoted.

8 Ibidem, p.24.

9 Bibó István, A kelet-európai

kisállamok nyomorúsága , Kriterion, Bukarest-Kolozsvár,

1997, pp. 38-41.

10 Bloom, William, Personal Identity

and International Relations, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge,

1993, p. 55.

11Bratu, Traian, Politica nationalã

fatã de minoritãti. Note si observatiuni, Cultura nationalã,

p. 8-9.

12 Livezeanu, work quoted, pp.41-63.

13 Verdery, Katherine, Transylvanian

villagers, University of California, Berkley-Los Angeles-London, 1983,

p. 345.

14 Mikó Imre, Nemzetiségi

jog és nemzetiségi politika, Minerva, Kolozsvár,

1944, p.427.

15 Official Gazette, nr. 282 of March

the 21st 1923.

16 Ioan Scurtu, Ion Bulei, Democratia

la români 1866-1938, Humanitas, Bucuresti, 1990, p.27.

17. Mikó Imre, A román

kisebbségi statútum, Gloria, Kolozsvár, 1938,

see: Mikó Imre.

18 Nagy Lajos, A kisebbségek

alkotmányjogi helyzete Nagyromániában, Székelyudvarhely

[Odorhei] 1994, p.117.

19 The Concordate in: Official

Gazette, no. 126 of 1929.

JSRI

• No.3 /Winter 2002 p. 129

20 Jakabffy Elemér, A konkordátum, in: Magyar Kisebbség

VIII, 1929, p.444

21 Bratu, work quoted, p.14.

22 Jancsó Elemér, Az

erdélyi magyarság életsorsa a nevelésügyek

tükrében 1914-1934 , Budapest, 1935, p.13.

23 Cf. B. Kovács András,

Szabályos kivétel, Kriterion, Bukarest-Kolozsvár,

1997, p.27; Popa-Lisseanu, Gheorghe: Sicules et Roumains: Un procés

de dénationalisation, Socec, Bucarest, 1935., p.5; Russu I.I.:

Românii si secuii, Ed. Stiintificã, Bucuresti, 1990,

p.137.

24 Ghibu Onisifor: Prologomena la o

educatie româneascã, Culturã româneascã,

Bucuresti, 1941, p.341.

25 Nagy, work quoted, pp.135-136.

26 Balogh Júlia, Az erdélyi

hatalomváltás és a magyar közoktatás

1918-1928, Püski, Budapest, 1996, p.79-80.

27 R. Szeben András, Az erdélyi

magyarság népoktatásügyének statisztikai

mérlege a másfél évtizedes román uralom

alatt, in: Magyar Statisztikai Szemle XII, 1934, p.852.

28 Salacz Gábor, A magyar katolikus

egyház a szomszédos államok uralma alatt, Aurora,

München, 1975, p.66.

29 See Gheorghe Iancu, Contributia

Consiliului Dirigent la consolidarea statului national unitar român

(1918-1923), Dacia, Cluj, 1985.

30 Ghibu, work quoted, p.314.

31 Barabás Imre, A romániai

magyar nyelvû oktatásügy elsõ tíz éve

1918-tól 1928-ig in: Magyar Kisebbség, VIII, 1929, p.79.

32 Constantin Anghelescu, Activité

du ministère de l'instruction 1922-1926, Cartea româneascã,

Bucuresti, 1928, p.56-58.

33 See Ioan Scurtu, Gheorghe Buzatu, Istoria

românilor din secolul XX, Aideia, Bucuresti, 1999.

34 R. Szeben, work quoted, pp.885-886.

35 Ibidem, p.852.

36 The data used in the tables are drawn

the works quoted and from: The Statistics on Romanian Education for the

School-Years 1921/1922-1928/1929, Ministerul Instructiunii, al Cultelor

si Artelor, Bucuresti, 1932, p.493-494.

37 Balogh, op.cit, p.92-93; Jancsó,

op.cit, p.355-356

38 Ibidem.

39 Ibidem.

40 Ibidem.

41 Ibidem.

42 Same note 36.

JSRI

• No.3 /Winter 2002 p. 130