Delia Despina Dumitrica

| Key words: the Uniate-Orthodox conflict, Romanian Orthodox Church, Catholic Church, ideological conflict, identity |

Uniate /vs./ Orthodox: What Lays behind the Conflict?

A conflict analysis

| previous |

Abstract: The current paper investigates the Romanian Uniate/ Orthodox conflict from the perspective of peace and conflict studies, making use of an interpretation of Johan Galtung's conflict theory and his proposed analysis tools.2 The aims are to contribute to a more comprehensive and multilateral understanding of this conflict in a wider context than the ideological one and hopefully to suggest some of the means of attenuating the conflict. "[...] the solution to a contemporary problem will never be found in a problem raised in another era, which is not the same problem except through a false resemblance." P. Veyne1 JSRI • No.3 /Winter 2002 p. 99 Introduction The first part of the paper reviews the emergence and development of the Uniate/ Orthodox conflict, proposing four different phases with particular characteristics and arguing that the conflict was shaped and re-shaped throughout these stages from an ideological to an economic level. Ariadna's thred is the quest for power (understood in all its dimensions). The second part of the paper will address the methodological issues, defining the main concepts used and putting forward an analysis of the conflict in view of the proposed methodology. Finally, the conclusion will attempt to peer into possible futures, mapping alternatives for conflict transformation laying ahead. 1. Brief overview of the Uniate/Orthodox conflict The

Uniate/ Orthodox conflict will be looked upon as a process, with several

phases and various levels of actors. The point of this overview is to

show how this process was impacted and shaped at several significant

junctures: 1918, 1945 and 1989. These three dates re-opened and re-defined

the conflict, with its three components: attitudes and behaviors of

the actors involved towards each other and contradictions born from

the competing goals of the actors; put otherwise, they re-defined not

only the agenda, but the actors themselves. Subsequently, the process

gradually affected the context 1.1. From 1698 to 1918: Conflict emergence In 1698, the Eastern Catholic Church (the Uniate Church) was born, upon an offer made by the Habsburg emperor Leopold I to the Orthodox Church in the Habsburg territory, including Transylvania: accept the Papal supremacy, the unleavened Eucharist bread, the existence of purgatory and the filioque doctrine. In return, the clergy and laity will enjoy the same privileges as Catholics, along with an exemption for the clergy from labor services and other fiscal duties.3 For almost 300 years, Romanians in Transylvania under Habsburg rule were second class citizens. No wonder that Leopold's offer was considered as the appropriate pragmatic solution by a minority at that time (Orthodox Romanians) in order to coexist and prosper under particular circumstances. The result was the Uniate Church, consisting of the Metropolitan province of Alba-Iulia and Fagaras with the seat in Blaj and headed by one Archibishop, with dioceses in Oradea, Lugoj, Cluj and Baia Mare and with around 200,000 believers.4 The Uniate Church preserved the main Orthodox JSRI • No.3 /Winter 2002 p. 100 rite, but was placed under the Vatican's jurisdiction.5 This phase may be seen as the non-violent emergence, delimitation and definition of the initial conflict, which opposed the Romanian Orthodox Church, on one side, to the Catholic Church and the Habsburg Empire on the other. Not surprisingly, the Romanian Orthodox Church did not happily accept this act. In fact, it never ceased to regard this conversion as a "betrayal", accusing that its members were lured by the Catholics, in a political stratagem, and the Uniates were rather perceived as the "victim" and were expected to rejoin the Orthodox rite as soon as this would be possible. 1.2. From 1918 to 1945: Re-shaping the conflict Once

Transylvania became part of Romania (1918), it seemed that the opportunity

for rejoining was finally there. However, the Uniate Church had by than

one and a half million believers, and was the wellspring of a dynamic

intelligentsia, deeply involved in the creation of Romanian nationhood:

politicians like Iuliu Maniu, scholars like G. Sincai, Petru Maior or

Innochetie Micu Clain. Concerned with the preservation of the Latin

roots of the Romanian people, the intellectual uniates (known as the

Transylvanian School) "decisively influenced the generation of

1848 revolutionaries who struggled to establish an independent Romanian

nation-state. Building on the recorded social memories and These tight links between Romanian nation-hood creation and the Uniate Church legitimized the latter within Romanian nationalist ideology7 and subsequently forced its acceptance as a separate entity by the Orthodox Church. Even more, as the ruling dynasty of the Hohenzollern was Catholic by birth (changing religion only due to political reasons), by 1926 the Uniate leaders were granted a position in the Romanian parliament, thus challenging the dominant traditional role of the Orthodox bishops over the ruling elite.8 The increasing Catholic political influence came to an end under Antonescu's government, when Orthodoxy became the means of mass manipulation (Orthodox values were used to mask the extreme nationalist and chauvinistic policy of the Iron Guard) and subsequently equated to being a "true Romanian". With the acceptance of the Uniate Church as a legitimized, independent actor, the Orthodox Church was no longer in conflict with the Catholic Church (within this particular context), nor with another state, but with a former insider who became an outcast. The ideological threat was therefore even greater, as the doctrines of the two rites were not that different. This could have not only confused the believers, who would not be able to see the reason for distinguishing so sharply between the two Churches (the threat of perceiving the Uniate as `brothers' or `siblings'), but it JSRI • No.3 /Winter 2002 p. 101 could have raised doubts on the centrality of Orthodoxy within the definition of the Romanian identity. By losing its centrality, the Orthodox Church would also lose its political influence and monopoly over religion (with everything deriving from lose of the status of `national church'). Thus the conflict was in itself altered: the fight was no longer to bring back the lost flock, but rather to keep the flocks apart in order to prevent any claim over power and resources. 1.3. From 1945 to 1989: A Latent Phase? After the second world war, under Soviet influence, the Church as an institution was secularized and put under the direct control of the State.9 Due to the "[...] Byzantine legacy of a `symphony' between secular and spiritual powers [...]"10 the Orthodox Church adhered to the policy of the new communist government and was granted a special position.11 Feeling more secure, the Orthodox Patriarch made it clear that the Uniates are part of the Orthodox Church, putting assimilation on the Orthodox (and state) agenda, stating at his enthronement: "At this moment, our thoughts turn to our Greek Catholic brothers, who until 250 years ago, were part of our flock... In these conditions part of the Orthodox flock in Transylvania, threatened with death, joined the flock of the tyrannical wolves and they have not yet had the courage to return to the Mother Church [...] Be true Romanians, like your forefathers... return to the ancestral Church, the Church of your and our forefathers."12 With the Concordat abolished, the absorption process of the Uniates started in October 1948, when thirty-eight Uniate priests made a formal request to the Patriarch for rejoining the Orthodox Church. These priests were carefully selected by the government and, in spite of the protests of the Apostolic Nuncio and of some other Uniate bishops, the reunification proceeded. The assembly's decision was confirmed by the Government in December of that year. The reunification process was not as easy as it might have seemed and over six hundred churchmen were imprisoned.13 However, once accomplished some of the Uniate properties were nationalised and some were transferred to the Orthodox Church. On their part, the Uniate clergy and believers "conformed on the tacit understanding that, if given a chance, they would revert to Rome."14 and functioned unofficially, holding underground meetings, secretly appointing bishops and preserving its believers. In spite of the meetings between Romanian Orthodox bishops and Ceausescu with the Pope in the `70s, the Uniate problem remained unresolved. Both Orthodox Church and the state saw the matter as closed - legally and ideologically, solved through the reconversion. However, failing to acknowledge that the contradiction still existed did not mean that the conflict was over once and for all. This phase of denying the conflict by imposing an authoritarian solution was indeed JSRI • No.3 /Winter 2002 p.102 violent and aggravated the attitudes of the actor whose mere existence was denied. 1.4. From 1989 onwards: Control over resources. With the demise of communism, the Uniate Church self-restored on the very last day of 1989 (recognized by the government in April 1990) and reclaimed its nationalized properties, as well as those transferred in 1948 to the Orthodox Church. At this point in time, religious freedom has been restored and secured in the legal framework; but at the same time, the Orthodox Church preserved its role as the "National Church of Romania" and openly reclaimed its centrality in the definition of Romanian identity. It was hard to deny the Uniate their right to existence, but at the same time it was easy to influence the public agenda on behalf of the Orthodox Church. As

a result, after the euphoria of the first moments of liberty, when the

Orthodox Church promised the return of Greek-Catholic properties,15

attempts to solve the restoration problem failed. The Orthodox party

had no interest in the dialogue, claiming legal ownership over the respective

properties. On the other hand, Uniates lacked any documents for their

request, as these were destroyed after 1948. In this vacuum favored

by the weak legal system, rumors of "unpatriotic" conduct

of the Uniate members (due to their affiliation with the Pope) fed the

nationalistic feelings against the Several attempts to reconcile the two churches' claims over the same resources failed. A 1990 mixed joint commission set up by a governmental decree to investigate the disputed cases did not meet until 1998 and failed after five meetings in 1999. Because of this decree, courts may refuse to consider lawsuits on the claiming of property. A 1993 document signed between Orthodox and Uniate Churches regarding properties was rejected by the Romanian Greek Catholics. A 1995 meeting between the Orthodox Patriarch and the Uniates was doomed to failure because of the unfair discussion set up by the Patriarch.16 In 1997, a proposal by a Christian Democrat senator on the restoration of Uniate properties in places where there still exist important Uniate communities was boycotted by the Orthodox community and did not materialize. A 1998 meeting between the two churches to reach a compromise failed once again.17 The 1999 visit of the Pope to Romania was a widely covered event, however with no direct consequences on the Uniate _ Orthodox conflict, except at the declarative level. In 2001, two Uniate parishes have sued the Romanian state to the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR). JSRI • No.3 /Winter 2002 p. 103 2. Conflict analysis Building upon the conflict theory developed by Johan Galtung, one of the founders of modern peace studies, the current analysis seeks to apply an interpretation of the theoretical framework to a concrete situation. As with any analysis of the kind, the limitations reside in the human inability to take into account all aspects of the conflict, due mainly to its complexity. 2.1. Defining concepts How is conflict defined in this paper? The protean nature of the concept infringes upon the development of a widely accepted definition, though some common elements enable understanding and mutual completition between the various schools of thought. On the same line with Galtung18, this paper considers conflict as a clash between incompatible, overlapping goals, constructed in a triadic manner within a temporal dimension and summing up the attitudes/ assumptions, the behaviors, and the contradictions involved. (Figure 1) The three corners of the conflict triangle are in correlation, reinforcing and completing each other.

Defining conflict is a tricky task in itself, as the word bares negative connotations from its daily over-use, especially in the media. Current research see conflict as an inherent element of human development19, one of the elements that induce transformation, as during the process, change comes about. From this perspective, conflict may be the opportunity for a positive change or transformation to occur.20 Not being good or bad per se, but rather becoming negative or positive through how it is handled by the participants, conflict is formed around a contradiction, involving different views, feelings and targets. Thus, rather than seeing conflict as a monolithic construct, this paper considers it as constantly changing - a process - re-defining the actors and contradictions involved. (Table 1) Though conflicts may arise within one individual or between two or more individuals, the present paper will consider conflict on the collective level - conflict between communities. A community is here defined as a group of people sharing some common collective values, rules and purposes, as well as a sense of belonging to that particular group. Communities might behave/ act homogeneously without this implying that they are indeed perfectly homogeneous. But at the same time, communities might be split and act heterogeneously, without this implying that there is no longer a community. Analysis should therefore pay particular attention to communities as a whole and at the same time as potentially factional. JSRI • No.3 /Winter 2002 p. 104

Table 1. Mapping the process of the Uniate/Orthodox

conflict JSRI

• No.3 /Winter 2002 p. 105 Conflict on this level automatically involves more than two actors, because local communities are integrated within a broader society and interconnected through various channels.21 Local communities might however share in common certain similarities/ features, like religion or ethnicity for instance. Thus the identity may be local and also on a larger scale, with individuals/ communities remote geographically, yet having something in common. Minorities are hence defined here as a group of people sharing certain features — features that are essential to building the collective identity, as well as a feeling of appurtenance to that specific group, and whose access to power and self-governance is conditioned by another group. Last, but not least, individuals have multiple identities and appurtenances that cross ethnic, religious and cultural boundaries.22 However, as the complexity of a conflict increases proportionally with the number of the actors involved - thus turning its analysis into an almost impossible task - it becomes necessary that a certain degree of generalization occurs (and this is how Table 1 should be read). If conflict is defined as having a temporal dimension, this implies at least a beginning - the formation of the conflict - and a transformation. What about a solution? A beginning implies an end, a solution - but is that really the case? Can a conflict between two communities have a solution that would not only resolve the contradiction, but also annul the attitudes and the behavior in the long term for all the actors involved, on both collective and individual levels? As the attempt to impose a solution through authoritarian means in phase 3 shows in the current case study, solutions are not final unless - according to Galtung - they are "(1) acceptable to all actors, (2) sustainable by the actors"23 (actors being interpreted here as communities - leaderships and individuals). Considering that the dichotomy beginning/end, problem/solution instead of helping the overcoming of the conflict, rather fixes the conflict upon itself, thus prohibiting positive progress, the present paper looks at conflict as a transformation processes, where changes are happening at all times shaping both the conflict and the involved actors. Instead of solutions, this perspective proposes that positive handling of conflicts should be viewed as tools that help the actors overcome the disagreement, the attitudes and the behavior associated with conflict. "But basically, conflict transformation is a never-ending process. Old or new contradictions open up. Negative, or hopefully positive, conflict energy of the A [attitudes] and B [behavior] varieties is continually injected into the formation. A solution, in the sense of a steady-state durable formation is at best a temporary goal. A far more significant goal is transformative capacity, the ability to handle transformations in an acceptable and sustainable way."24 2.2. Analysis Based on the above-described concepts, the conceptual analysis starts from investigating the potential JSRI • No.3 /Winter 2002 p. 106 number of actors and hypothesizing their presumed interests in the conflict during the fourth phase - since 1989 to today. The methodology contains an analysis of attitudes, beliefs and contradictions for each of the main actors. As the conflict (and the actors) are not in a vacuum, there is a need for taking into consideration the structural and cultural implications and limitations that affect the conflict.25 Table 2 describes the main actors involved in the present phase of the conflict and attempts to map their potential interests (as inferred from their actions). It also takes into consideration the structural constraints, namely the inherent features of the structure (be it local community, state or international system _ in terms of institutional and cultural constraints) that may exert pressure and thus re-shape the conflict. The table however should not be interpreted as a homogenization of actors: within all actors there have been individuals that have expressed different attitudes and behaved differently from their group (for instance, the case of the Metropolitan Bishop of Timisoara, Nicolae Corneanu who, opposing the Orthodox Church's hierarchy, gave back - or at least supported the liturgy by providing worship places - some of the properties to the Uniate Church, among which is the Cathedral in Lugoj).

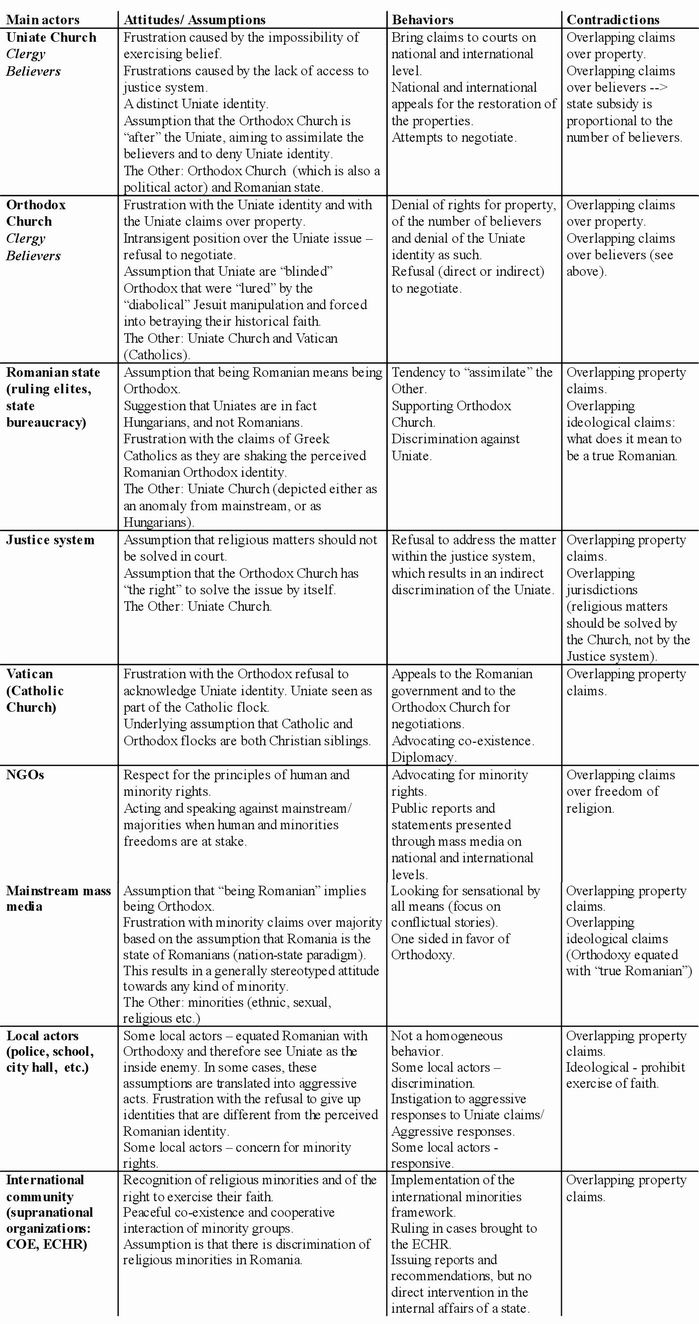

Table 3 makes use of the triadic nature of the conflict (see figure 1 above) to analyze the attitudes, behaviors and the disagreement for each of the main identified actors. While asserting the attitudes/ assumptions and behaviors of others is always a matter of subjectivity, some general patterns can be inferred from the explicit actions of the actors. The analysis in Table 3 is based on subjective inferences from the observation of the actions of the actors involved. It is an interpretation of the main actors and their acts in connection to the conflict. Instead of conclusion: Paths laying ahead. Transcending the ideological level may open new opportunities for a "detensioning" of the Uniate/ Orthodox relations and enforcement of religious minorities rights. But the transformation of the conflict from around one concerning an ideological disagreement to an economic disagreement (overlapping claims over property) does not imply that the ideological rhethorics is not present on the level of attitudes and behavior. However, ideology does not constitute the core of the conflict anymore. So where can the conflict go from here? If conflict is seen as a transformative process, than what are the main factors able to influence its transformation towards a positive outcome? Coming back to figure 1, if conflict is to be seen as the inter-linkage of attitudes/ assumptions, behaviors and contradiction, than pressing upon either one or all of the corners can lead to a reshaping of the conflict. A first possible path would be when attitudes and behavior remin the same, while the contradiction is not resolved. In the absence of any progress or any (at least JSRI • No.3 /Winter 2002 p. 107 Table

2

partial) agreement, the situation is prolonged in the hope that it will become the status quo. But this would only deepen the frustrations of the Uniate clergy and believers, which in the long run is neither beneficial, nor productive for any of the actors involved. It may be that attitudes and behavior become more radical, and therefore no agreement can be reached on the contradiction. If the structure remains the same (meaning the legal framework, the behavior of the ruling elites and the refusal of the judiciary to deal with the problem), than it is more likely that the attitudes and behaviors of the two religious communities will be aggravated. Mutual negative feelings will feed hate speech and prejudices, which on their turn will increase the likelihood of a discriminating behavior. However, the pressures from the international organizations and NGOs may induce a positive structural change on the level of Romanian central state apparatus. But change may come through yet another corner: behavior. Should behavior change - either by itself or under external pressures - the content of the disagreement can be approached with various alternative solutions. By finding a common ground for tackling the disagreement, attitudes will be increasingly altered (positively or negatively). If attitudes become more positive, than favourable conditions for a more comprehensive solution for the contradiction could be created. Last,

but not least, another approach could be conceived if the structure

changes and the contradiction is addressed, namely the judiciary under

the pressure of Of course, possible conflict transformations could be looked upon from yet another pespective: community and leadership levels. The influence of actors such as the mass media, NGOs, political elites - on both national and local levels - and local actors could provide the glue for a positive conflict transformation, or could deepen the crisis. Behavior could be addressed on the level of the local communities through a more creative approach, like for instance agreeing to use the same worship facilities for both confessions in places where there is only one church - and intuitively it might seem as easier to find a common ground and to start building in local communities; subsequently, the pressure from the bottom upwards could enforce a change in the behavior of the leadership of the two Churches. Political elites, the justice system and local actors have the power to address the legislative and the judicial aspects - creating favorable conditions for the positive transformation to occur by removing some of the structural constraints causing the imbalance between the two Churches. JSRI • No.3 /Winter 2002 p. 110 Table

3: Analysis of the attitudes/ assumptions, behaviors and contradictions

as inferred from the explicit actions of the actors.

JSRI • No.3 /Winter 2002 p. 112 Notes: * Delia Despina Dumitrica holds a MA in Southeast European Studies and is currently working towards achieving a second Masters degree in Peace and Conflict Transformation at the University of Tromsoe, Norway. Her research interest is nationalism in Southeastern Europe. Any comments on the paper can be send to deliadespina@hotmail.com 1 P. Beyne, "The Final Foucault and His Ethics", Critical Inquiry, vol. 20, no.1 (1993), p. 2 2 See Johan Galtung. Peace by Peaceful Means. Peace and Conflict, Development and Civilization. PRIO, Sage Publications, 1996 3 Perspectives about the conversion may vary. The Library of Congress Country Studies accessible via World Wide Web states that the conversion was at many times done against the wishes of the believers and that in fact the Romanian Uniate clergy did not receive the same privileges as Catholic priests. (Information accessed last on 12.09.2002 at http://www.workmall.com/wfb2001/romania/romania_history_the_uniate_church.html) 4 According to Janice Broun. Conscience and Captivity: Religion in Eastern Europe. Washington DC: Ethics and Public Policy Center, 1988, p. 202. By 1773, there were already 2,294 Uniate priests and approximately six hundred thousand believers [David B. Barett (ed.). World Christian Encyclopedia, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1982, Romania, p. 367] 5 "Briefly, the substance of such a union was this: the Orthodox Church or community entering upon such a union retained its liturgical, disciplinary, spiritual and theological tradition (identical to that of Eastern Orthodoxy in general), while accepting full communion with the Roman Catholic Church." (Serge Keleher, "The Romanian Greek Catholic Church", Religion, State and Society, Vol. 23, No. 1, 1995) 6 John S. Micgiel, ed. State and Nation Building in East Central Europe: Contemporary Perspectives. New York: Institute on East Central Europe, Columbia University, 1996. 7 Without however assimilating the Uniate as a defining element of Romanian identity. Rather, the legitimation was rather contextual and served the recognition of the Uniate Church as a distinct identity by the Orthodox Church. The Romanian identity is essentially Orthodox, this playing towards the collective forgetting of the role of the Uniate - for instance, the Transylvanian School intelligentsia is not linked to the Uniate identity (enforced "collective amnesia" leads to collective forgetting). 8 The privilege of 1926 was granted to four Eastern Catholic bishops: the heads of the Roman Catholic Church, the Lutheran Church, the Reformed Church and the Unitarian Church. (Paul Mojez. Religious Liberty in Eastern Europe and the USSR. NY: Boulder, 1992, p. 313) 9 The Vishinski Plan provided for budgetary salaries for the clergy, liquidation of dissidents and infiltration of pro-soviet priests, restrictions on the religious activities of worship. (Robert Tobias. Communist - Christian Encounter in East Europe. Indianapolis: School of Religion Press, 1956, p. 317) 10 Earl E. Pope: "The Contemporary Religious Situation in Romania" in Dennis J. Dunn (ed.) Religion and Communist Society. Berkley: Berkley Slavic Specialties, 1983. 11 The Patriarch Justinian had close ties with Gheorghe Gheorghiu Dej, as while chased by the Nazis, the latter was hidden and protected by Justinian. More than this, Dej was himself from an Orthodox family and his father was a priest. In his government, the Minister of Education and some other members were Orthodox. Justinian worked closely with Dej on the "re-education" of the clergy (see Robert Tobias, 1956, p. 325) 12 Robert Tobias, 1956, p. 327 13 Alan Scarfe states that 400 priests were executed. Regardless of their number, it is obvious that the Uniate clergy was severely affected and that cruelty in the treatment of the Uniate believers was hardly necessary. (Alan Scarfe, "The Romanian Orthodox Church" in Pedro Radamet (ed.) Eastern Christianity and Politics in the 20th Century. London: Duke University Press, vol I, JSRI • No.3 /Winter 2002 p. 113 1988, pp. 208 - 232). According to the Religion Around the World website, "some 14,000 recalcitrant priests and 5,000 adherents were arrested, at least 200 believers were murdered during incarceration and many others died from disease and hunger." Source: Library of Congress Country Studies. (Information accessed last on 12/09/2002 at http://atheism.about.com/library/world/KZ/bl_RomaniaUniate.htm) 14 Janice Braun, 1998, p. 206. An attempt in 1956 to appeal for the restoration of the Uniate Church was buried under a new wave of persecution. In 1980, a clandestine Uniate committee appealed to the Madrid Conference of the CSCE for the restoration of their church with no success. 15 The Greek Catholics claim from the Romanian state: 2,000 parishes, 1,800 churches, cemeteries, chapels and presbyteries, 11 monasteries, 5 Episcopal residences, 3 theological seminars, 20 schools, 6 hospitals, 4 orphanages, 3 retreat houses. 16 The Greek Catholics were required to renounce everything that they had achieved since 1989 and to start everything from the beginning by setting up a mixed commission. (Dr. Vincent Cernea:"The Greek-Catholic Church: The current situation" in Human Rights without Frontieres, No. 3&4, 1996) 17 According to the coverage of the meeting by a journalist for Romania Libera daily, "the Orthodox part gained everything while loosing nothing, as the Greek-Catholics lost everything, while earning nothing." (29 October 1998) 18 Johan Galtung. Peace by Peaceful Means. Peace and Conflict, Development and Civilization. PRIO, Sage Publications, 1996, pp. 70 - 80 19

Psychodynamic theories of human development see it as "confrontations

between growing individual demands and the demands of the social role.

They emphasize how the individual 20 Galtung mentions that in Chinese, crisis has a double meaning of danger and opportunity. 21 Even if some communities may be isolated from the rest of the society (either self-imposed, as a result of a coercive act or due to geographical circumstances), total isolation is impossible to be conceived in today's world. Even if a community might manage to become fully self-sustainable, it will still be caught within the institutional setting of a state and thus forced into at least maintaining some form of relationship with these state structures. Even if this is done only on the level of the ruling elite, spillovers are likely to occur. 22 An individual may be a member of the community X, a mother, a lawyer, with a particular ethnic and religious identity, etc. In cases when communities are defined along ethnic or religious lines, some of the identities might overlap. 23 Galtung, 1996, p. 89 24 Galtung, 1996, p. 90 25 Structural constraints are those emerging from the institutional setting (legal framework, local organization of the community). Structural constraints are derived from the culture of that particular setting (culture being taken in its broadest form of norms, rules, rites, values, patterns etc.) JSRI • No.3 /Winter 2002 p. 114 JSRI • No. 3/Winter 2002 |

| previous |